So rare is it to find a talent that transcends genre or prototype, producing a distinct voice and flare that can be identified by simply glancing at the screen. A filmmaker’s task is not just to tell the story of a few fictional or fictionalized people through a series of set events, but rather to express the innumerable emotions that are coursing through their veins and to blur the thin partition that separates fiction and reality. The shroud that veils the audience will dissipate in the rarest of circumstances when a film’s emotional core transcends the screen and reaches a viewer on the most intimate of levels. When such a feat can be accomplished, a filmmaker is not only revealing the inner workings of his or her characters’ souls, but that of his or her own as well.

:format(jpeg)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/54992921/687799390.0.jpg)

Sofia Coppola portrays a faint, dulled visual imagery that can fulminate into something wholly intractable – as her worlds exceed the characters’ grasp. She explores characters that are thrust in the mire of a depressive brain-fog and the inescapability of modern-day loneliness. Simply by using her titles, many of her characters are lost in translation or searching for somewhere without knowing where that lofty place is. She does not condemn their inner sorrow, instead opting to give them the space to figure it all out. We watch two lost souls find each other and therefore themselves among the hectic streets of Tokyo, an actor leading an existence void of meaning riding his black Ferrari along the same dirt-swept loop, a teenage girl forced to meet the expectations of her society to further the interests of her family, completely alone in a distant land. Many of Coppola’s characters are isolated, whether it is their choice or not, and due to this, they do not experience the world around them as others do.

The Lisbon sisters of “The Virgin Suicides” are gazed upon and gawked at until they disappear into a prison brought upon by the stifling nature of condemnation. The demands of their society do not line up with any fathomable stretch of reality and therefore they are punished, chided, and hidden away for eternity – until they do the one thing they can muster. Those around the Lisbon sisters propped them up as inhabiting a special space that was impenetrable – most notably seen as the teenage boys whose perspective the narrative unfolds from becomes visually palpable. The camera gazes at them from behind, often obscured by a gate or a shuttered window, and makes these young women inaccessible. In truth, they are simply human in every way – occupying areas of vast gray in comparison with the black and white world of suburbia.

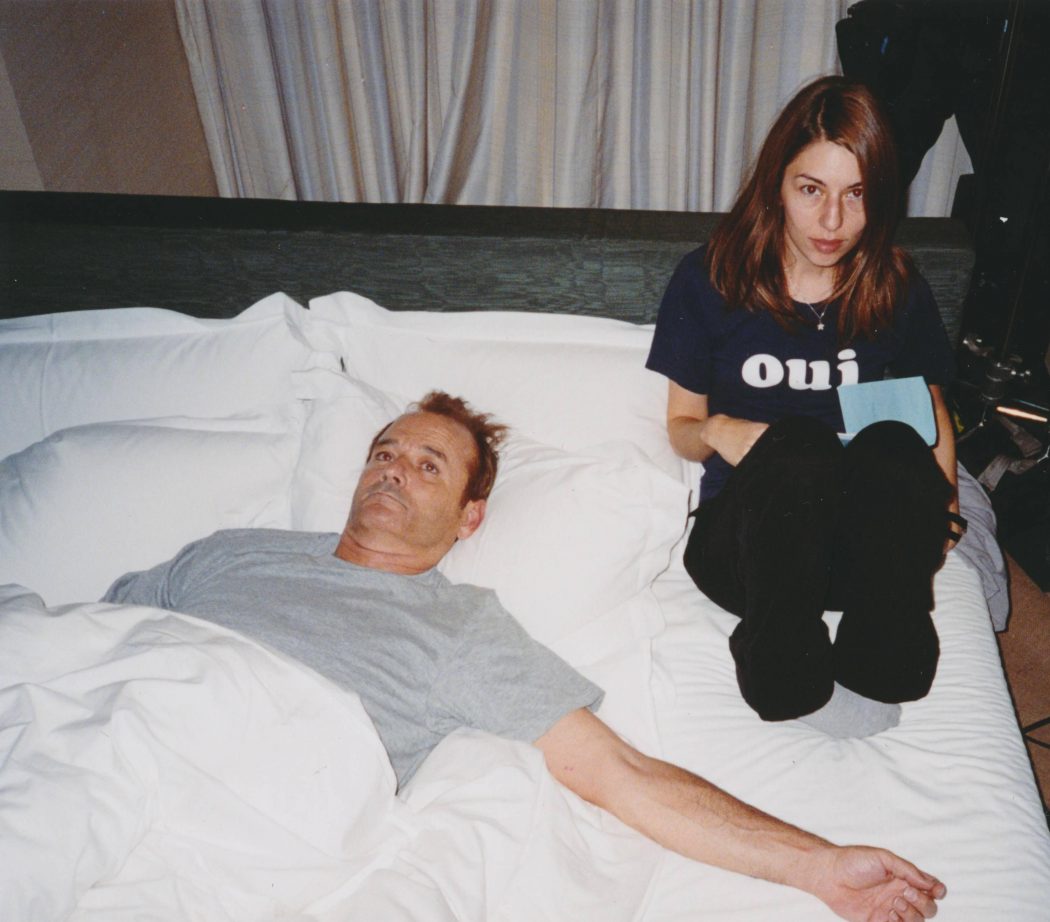

That perspective rapidly switches in “Lost in Translation” – Coppola’s most widely-viewed and celebrated film – where the viewer takes upon the perspective of the protagonists that have become swallowed up by their respective realities. Two Americans living in Japan cannot seem to create any tangible relation with anyone else – an overabundance of stimuli creates ennui. Bob Harris (Bill Murray) cannot seem to comprehend who he has become, an aging actor that has lost that once lively spark he shared with his wife. He has love both for her and their children, but sometimes love is not enough to propel one forward, however, it might be enough to drown him. Charlotte (Scarlet Johansson) is too young to know who she truly is, a husband dominated by a busy photographer’s schedule, leaving her alone drifting among the peripheries of the frame. Then something magical happens, Bob and Charlotte find each other. Balance is restored and they have meaning for a fleeting moment of jubilation until it passes. Still, it happened and that cannot be erased.

“Marie Antoinette”, blaring with style from its waking moments – to the tune of Gang of Four’s “Natural’s Not in It” – then overflowing like the silky, golden champagne upon the stack of assorted glasses. The film is bedecked in color, as the eponymous Austrian-born Queen of France gains a place in a new country, earning friends and building relationships until she is forced to say her final goodbye. At the start, she has no one other than the Austrian ambassador to France (Steve Coogan) as she must embrace the whispers of the onlookers regarding the faults of her marriage or her status as an “Austrian spy”. Yet, once she meets her stride, her glowing inner enthusiasm finally is able to shine through. The pageantry of it all is fiercely bold and the anachronisms – the soundtrack most obviously – make it clear that Coppola’s story is in name about 18th century France, but in reality, it transcends time and space. Rather it taps into universal truths, it is just the tale of a lonely teenage girl whose circumstances far outstrip what can be expected of one person to cope with.

“Somewhere” is perhaps Coppola’s most understated feature, functioning as a miniature “Lost in Translation” while also extending beyond its boundaries in many meaningful ways. Those who are isolated are held tight to that same roundabout track, its hold cannot subsist without a strong impulse. Johnny Marco (Stephen Dorff) cycles through empty relationships in the same way he speeds along the streets of Los Angeles, meandering – as is illuminated by the beautifully photographic cinematography of Harris Savides and set to the hushed tones of Phoenix. Cleo (Elle Fanning) serves as that impetus to Johnny’s emptiness, as his daughter provides him with a meaning that all the endless procession of models and riches of his glamour has deprived him of. He realizes this too late, yet he can still find his way, he can still go somewhere, and his daughter will surely be there at his side.

Coppola’s filmography is extensive and diverse; however, these four films underscore the extent to which her true style reckons with emotion. We see this in the low angle shots weaving through tall grass or the handheld shots following closely behind our unknowing characters while the score swells. Sometimes trumpeting hope, other times accentuating the fading glow of outer beauty entangled amongst inner torment, or even displaying the horror of the silent thrashings against a world that refuses to compromise. In the end, these tiny personal stories have no less impact than the scope and scale of epic proportions that her father, Francis Ford Coppola, routinely exhibited. For many, the hollow fog that hangs over these films can provide comfort rather than despair. As we look to Coppola for these pressing answers, she silently divulges that sometimes good ones do not exist, but also makes it clear that this truth should never halt the search.